When is it acceptable to break the law? Do some regimes, by the harm they cause, demand opposition? When does resistance become a moral obligation?

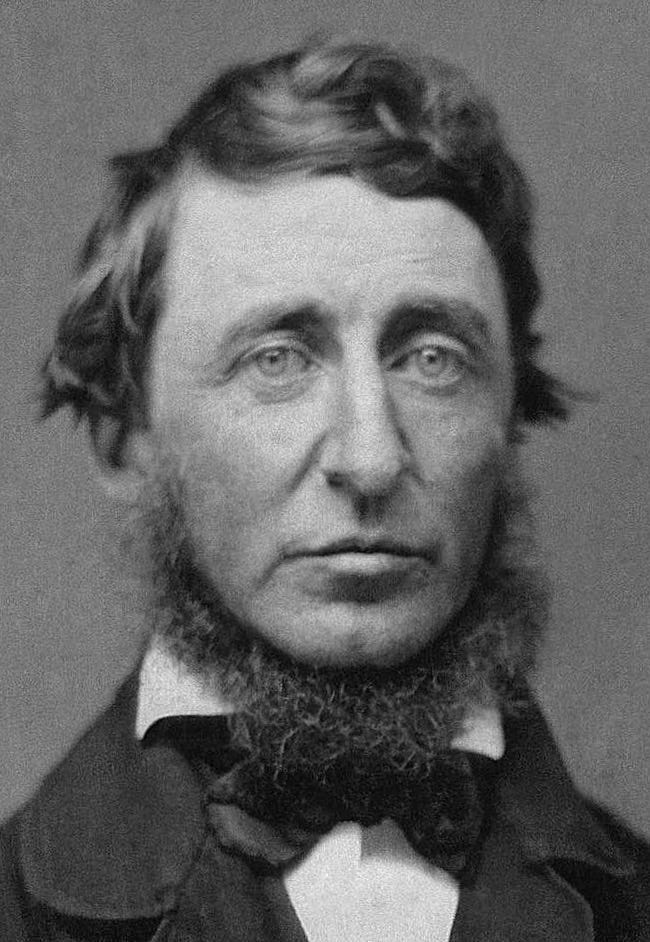

These questions have a long history in the United States, which was founded by a violent protest movement. Perhaps the best-known writer to tackle the topic was Henry David Thoreau, a philosopher from Massachusetts.

Thoreau’s writings are remarkable for their reinterpretation by later generations. One of his essays is usually titled “Civil Disobedience.” But when he first published it in 1849, Thoreau called his work “Resistance to Civil Government.”

The title change was not mere semantics. “Resistance” denotes active opposition, compared to the passive “disobedience.” Thoreau likely chose his words with intent, since many New England preachers urged “disobedience” against the Mexican War (1846-48) and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The latter law required all U.S. citizens to help perpetuate slavery by returning escaped individuals to alleged owners. The main point of Thoreau’s essay was that individuals have a higher obligation to their consciences than to the laws of the land.

According to late political scientist Russell Hanson, Thoreau’s title was tamed due to the wishes of his sister and his publisher to give the writer a more peaceful legacy, after the Civil War made Americans wary of more violence. Thoreau died in 1862, and a revised 1866 edition of his essays became the standard text that circulated around the world.

The great Russian author Leo Tolstoy helped popularize Thoreau through the efforts of his English-language publisher. Tolstoy’s business partner had to emigrate from Russia after he criticized the Tsar’s persecution of a Christian sect that refused to serve in the army. The publisher included Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience” along with translations of Tolstoy’s works in a series of cheap tracts marketed to working-class readers.

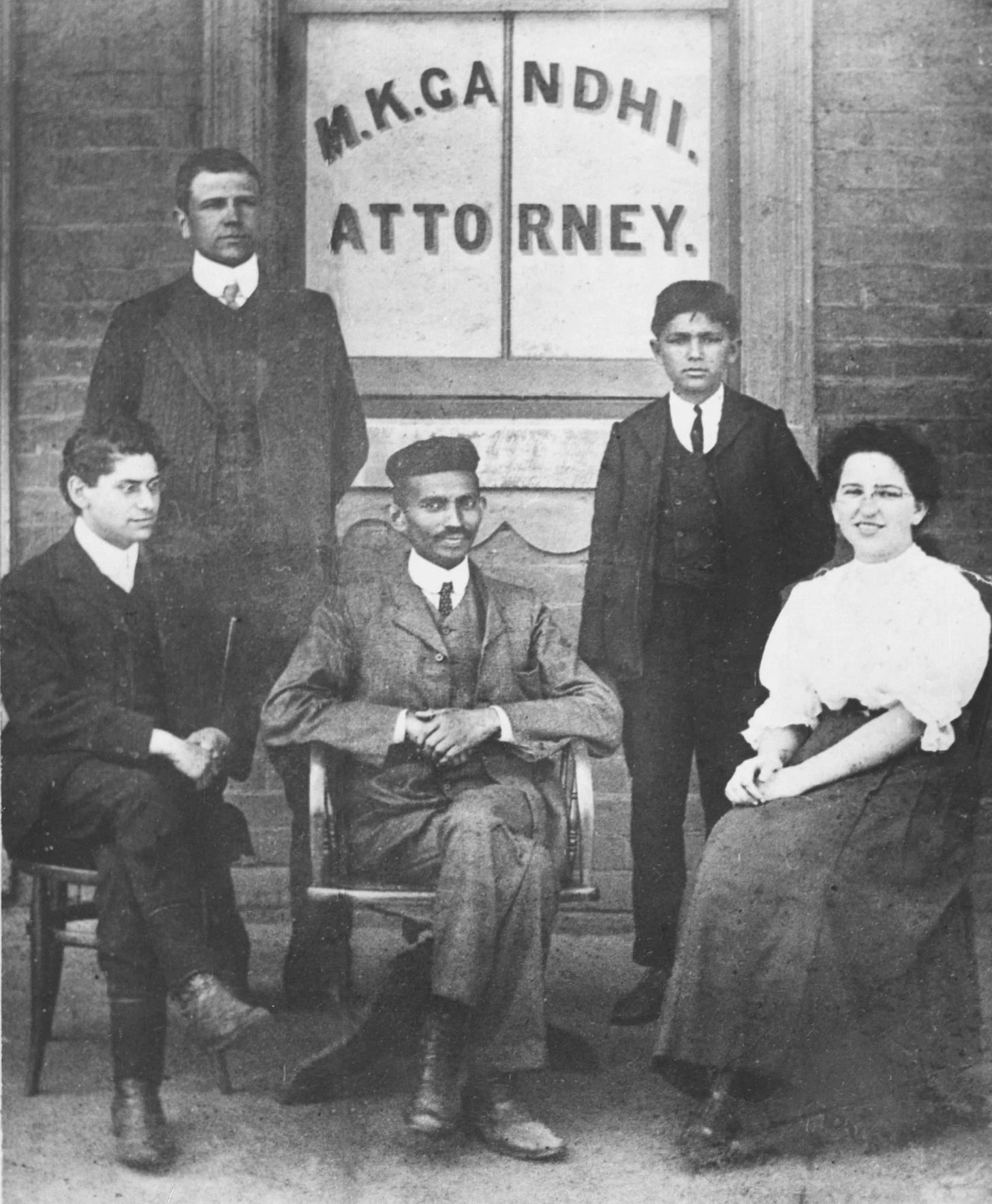

It was probably by this path that Thoreau came to the attention of Mohandas Gandhi, just as he began his protest against Indian discrimination in South Africa. Gandhi already had a concept of resistance to the state — Satyagraha (literally, holding firm to truth) — but he was looking for a way to translate his ideas into an English catchphrase. “Civil Disobedience” seemed to fit with Gandhi’s nonviolent methods.

But there were important differences between Gandhi’s and Thoreau’s philosophies. Whereas Gandhi stuck to peaceful practices alone, Thoreau embraced violence in his writings.

Thoreau’s essay on disobedience begins by noting that the best government is that which governs least. All organizations cause “friction,” which impedes the freedom of ordinary people. But in many cases, the government “does enough good to counterbalance the evil.” It is only when “friction comes to have its machine, and oppression and robbery are organized,” that Thoreau proclaims: “let us not have such a machine any longer” (4).

Thoreau’s recommendation for resistance was to stop paying taxes. He took up this method himself and was jailed for his decision. The tactic of tax delinquency could be a fitting form of protest in the age of Trump, because our chief executive has bragged about his failure to support the common good. In fact, Trump made the dubious claim that avoiding duties “makes [him] smart.” Perhaps the President’s skepticism about income taxes helps to explain why he has embarked on his absurd tariff adventure.

Thoreau does not stop at peaceful means of noncompliance. He writes:

“But even supposing blood should flow. Is there not a sort of blood shed when the conscience is wounded? Through this wound, a man’s real manhood and immortality flow out, and he bleeds to an everlasting death. I see this blood flowing now.” (10)

Thoreau saddled the blame for violent protest with governments that pursue harmful policies. He was concerned about mid-19th-century evils of war and slavery. Today we may notice Trump’s praise for a Russian warmonger, his pardon of the January 6th traitors, and his enabling of parasitic capitalists to the ruin of working people.

Thoreau was even more emphatic about embracing violence in “A Plea for Captain John Brown” (1859). He wrote about the man that many contemporaries called an insane terrorist:

“For once we are lifted out of the trivialness and dust of politics into the region of truth and manhood. No man in America has ever stood up so persistently and effectively for the dignity of human nature” (40).

This opinion set Thoreau apart from fellow Massachusetts literary giant Nathaniel Hawthorne, who called Brown a “fanatic” and concluded that “nobody was ever more justly hanged.”

But given the choice between defending property or liberty, Thoreau had no doubt about which was more just. In an earlier essay, Thoreau bemoaned that the “majority” of Americans “are not men of principle. If they vote, they do not send men to Congress on errands of humanity…It is the mismanagement of wood and iron and stone and gold which concerns them” (26). Finally, a man of integrity such as Brown had emerged, undeterred by the mortal consequences of his violent virtue.

Thoreau points here to a more fundamental split between his beliefs and Gandhi’s. Should protest take place through individual or collective efforts? Thoreau argued that a heroic figure could spark effective resistance. Gandhi — as well as Martin Luther King Jr. — shifted focus on the individual to the discipline of mass movements. It was perhaps this move toward political organization which allowed for the great success of Gandhi and King compared to the obscurity of Thoreau during his lifetime (Hanson, 49).

Still, the great 19th-century thinker’s condemnation of American politics continues to ring true today. In one of his last essays, Thoreau rejected his countrymen’s evident preference for money over morality:

“If a man walk in the woods for love of them half of each day, he is in danger of being regarded as a loafer; but if he spends his whole day as a speculator, shearing off those woods and making Earth bald before her time, he is esteemed an industrious and enterprising citizen. As if a town had no interest in its forests but to cut them down!” (Thoreau, 76)

We can see the wisdom of Thoreau’s environmentalism in this phrase, which reveals how far ahead of his times he was.

In an even more prescient passage, the American philosopher noted the pernicious effect of daily newspapers on his neighbors’ attention spans. The increased speed of information, now in morning and evening editions, was not making people more intelligent. Instead, the pace of media dulled readers’ capacities to process wisdom.

Thoreau believed that industry was making people dumber. In his words, “the mind can be permanently profaned by the habit of attending to trivial things, so that all our thoughts shall be tinged with triviality” (86). The comment is even more true of today’s social media feeds, its post-literate memes and TikTok dances, than news columns of politics and business during the 19th century. Thoreau was the first to use the term “brain rot,” which he adapted from recent instances of European potato rot.

Thoreau’s advice for counteracting this alarming trend: “Read not the Times. Read the Eternities.” Here, he was on firm footing. We must limit our indulgence in the trivial gossip of the day, so that we have time enough for texts that have survived centuries. In future blog posts, I will turn from the ills of our age to the insights of ancient texts.

In the meantime, the most effective means of protest could be Thoreau’s proposed withdrawal of support. This may involve denying votes or tax dollars to the current regime, but it could be still more effective to withhold attention. We may think of paying heed as the new currency in our age of big data.

Today’s primary threat to democracy appears to be oligarchy. Lack of attention and negative attention, which both aim to “zero” the value of companies owned by overreaching billionaires, seem to be the best paths forward. The American people appear to have grasped the necessity of resistance, as mass protests against Trump, Musk, and their associates continue to grow in popularity. This rising tide will not be easy to stop.

For further reading:

Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience and Other Essays (Dover, 1993)

Russell Hanson, “The Domestication of Henry David Thoreau,” in The Cambridge Companion to Civil Disobedience, ed. William Scheuerman (Cambridge University Press, 2021)